Illuminate the abyss: the innovative inventions of Dimitri Rebikoff coloured the underwater world.

When you step into a dive shop, it’s almost inevitable that the conversation will eventually gravitate toward the art of underwater photography. Scuba diving enthusiasts, at some point, find themselves eager to try their hand at capturing the mesmerizing beauty that lies beneath the azure waves. They enthusiastically display their underwater snapshots on smartphones, compact-camera screens, and various social media platforms.

The widespread fascination with underwater photography owes much to the accessibility of affordable deep-sea-ready cameras, camera housings, and lighting systems available today. From compact GoPro cameras ingeniously affixed to scuba masks or extending from buoyant selfie sticks to intricate setups designed for mirrorless and full-frame digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras, complete with advanced LED lighting, the primary limitation often boils down to a diver’s budget.

Yet, there was an era when the underwater world remained an enigmatic frontier, explored only by the boldest adventurers. Early divers embarked on daring endeavours, lugging colossal plate cameras tethered to wine-barrel buoys and manoeuvring them along the ocean floor in depths of up to 20 feet. Numerous challenges abounded, ranging from the rapid destruction of cameras and film by seawater to the optical distortions inherent in the aquatic environment. The notion of bringing lighting and electrical power into the depths of the sea remained a fantastical dream for most, seemingly reserved for the mythical city of Atlantis.

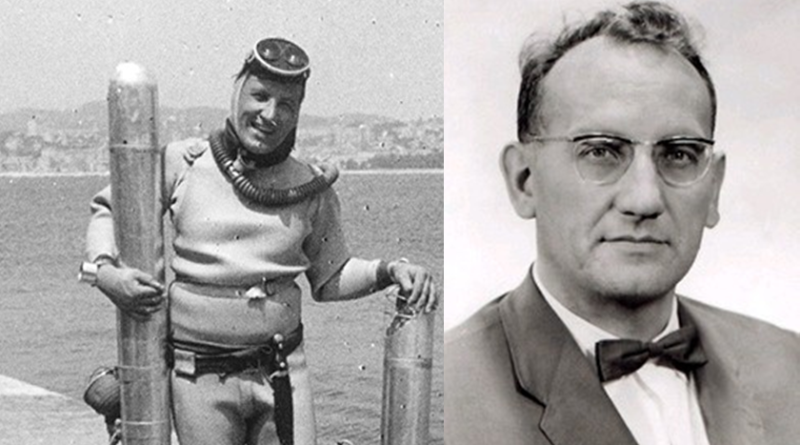

However, the aftermath of World War II witnessed a transformative period when photographer and inventor Dimitri Rebikoff, along with pioneers like Jacques Yves Cousteau, reshaped the landscape of underwater exploration. This era was a breeding ground for visionaries, including Rebikoff, Cousteau, Émile Gagnon, and a legion of other inventors and explorers, whose innovations in lighting, cameras, and life-support systems proved reliable even when submerged. Their groundbreaking work, complemented by a plethora of popular books, films, and TV shows, ushered in a new age of underwater exploration, encompassing scientific endeavours, recreational sports, entertainment, and commerce. This legacy has continued to flourish over the decades.

In fact, we owe the spectacle of cable TV’s annual Shark Week, featuring heart-pounding underwater footage of sharks, to the pioneering contributions of Rebikoff and his contemporaries. Without their advancements, this captivating event might have never come to fruition.

For Dimitri Rebikoff, the journey began on the rain-soaked streets of post-war Paris. He found himself struggling as a tabloid news photographer by day and moonlighting as an engineer after hours in a city newly liberated from Nazi occupation. It was during this period that Rebikoff caught the attention of Jacques Cousteau, thanks to his ingenious invention in 1947—an easily portable electronic strobe that also possessed waterproof capabilities, a feature tailored to his often-challenging working conditions.

Rebikoff secured French and Swiss patents for his groundbreaking creation, ultimately selling an impressive 10,000 units in France alone. He ingeniously adapted his water-resistant housings for use with 16-mm movie cameras. Between 1947 and 1949, Rebikoff successfully repurposed his strobe for various scientific and industrial applications. Notably, he applied it to the study of propeller cavitation in water tunnels and the examination of ships’ hulls in the vast expanse of the open ocean. In recounting his journey at a 1968 SPIE conference in San Diego, Rebikoff detailed receiving a call from the French Submarine Alpine Club, requesting the adaptation of his strobe and camera for underwater photography during scuba dives. The outcome exceeded expectations, producing the first razor-sharp, color-accurate underwater photographs of marine life, geological wonders, and archaeological treasures. Rebikoff attributed this success to the holistic design of a “complete integrated system,” wherein each component—camera, corrected lens, strobe light, controls, and housings—was meticulously crafted to work in perfect harmony, achieving the desired results effortlessly.

In the late 1940s, Jacques Cousteau entered into a contractual partnership with inventor Dimitri Rebikoff to create specialized equipment for his underwater expeditions. This collaboration blossomed, enabling Cousteau to produce his Oscar-winning film, “A World Without Sun,” and early TV shows with the aid of Rebikoff’s innovative lights, cameras, underwater housings, and one-person submarines. Rebikoff himself would go on to author approximately 27 books on the subject of underwater photography.

One of their remarkable achievements was the 1949 introduction of a high-voltage battery strobe light. Housed in an elongated plexiglass tube filled with clear transformer oil, it was positioned as far forward of the camera lens as possible to prevent illuminating the suspended particles between the subject and the lens. This groundbreaking strobe not only provided excellent contrast and definition in the center of each frame but also showcased the vibrant colors of marine life like sponges and coral in a manner that defied description.

However, Rebikoff’s innovative journey did not conclude there. Studies of fish eyes had revealed that traditional flat glass or plastic portholes were inadequate for satisfactory underwater photography. The plane diopter effect caused the portholes to function as 3.4 diopter magnifier lenses.

Collaborating with Alexandre Ivanoff of the Paris Museum of Natural History, Rebikoff invented the renowned Ivanoff-Rebikoff lens. This optical marvel was a reverse Galileo Telescope meticulously designed using two new types of optical glass to fully correct all aberrations while simultaneously increasing the focal length—a breakthrough in underwater optics that could be applied to various cameras, optical instruments, and even the human eye.

Rebikoff remained steadfast in his pursuit of enhanced underwater photography possibilities, focusing on integrated systems that included cameras, lighting, and tow vehicles. According to the International Scuba Diving Hall of Fame, which honored Rebikoff with induction, his underwater vehicle named “Pegasus,” unveiled in 1953, resembled a torpedo with handles and a camera mount. This innovation found use in scientific expeditions, where it explored and photographed fossil life beneath glaciers, and in the oil industry for ocean floor exploration.

The Pegasus, which could be operated either manned or unmanned, and its subsequent iterations solidified Rebikoff’s legacy in modern underwater photography, serving a wide array of purposes and applications. It formed the foundation for his company, Rebikoff Underwater Products, based in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where he settled in the early 1960s and spent the remainder of his life. With these vehicles, Rebikoff championed the concept of strip-scanning photogrammetry, enabling the parallel scanning of the seafloor in adjacent strips using high-capacity camera systems. This approach overcame the limitations of underwater visibility, which hindered large-area photography, such as that possible with aerial or space photography over dry land.

In a lecture on photogrammetry at a 1966 SPIE conference in Santa Barbara, California, Rebikoff elaborated on the applications of this technique, including undersea cable and pipeline surveys, stereophotogrammetric mapping of the seabed, photography of large submarines and marine life, archaeological surveys, and landing beach and approach assessments.

Dimitri Rebikoff, who passed away in 1997, once shared with Florida’s Sun-Sentinel newspaper that he conceived the Pegasus because he considered himself a “lousy swimmer” and faced difficulties maneuvering underwater while handling unwieldy cameras. His inspiration for the design came from early aeronautical engineers who observed the physiology of birds to understand flight. Rebikoff then began observing the movements of sharks, a testament to his inventive and visionary spirit.